Mathematics or Science?

As part of the program chair’s report for POPL 1992, Andrew Appel wrote a paper titled “Is POPL Mathematics or Science?” His paper measured how theoretical a conference is using the author ordering of the papers published. While this paper was meant to “provide some laughs”, I thought it was very interesting and reproduced the results for both the same data and for present-day programming languages conferences.

Most scientific fields usually order by the amount of work each author contributed, sometimes with other conventions, like students being listed first or the grant holder being listed last. Mathematical fields, however, typically order authors alphabetically, since small ideas are often instrumental in a paper, and it can be difficult to rank the importance of each author’s contributions. Computer science can go in either direction, depending on the subfield and the paper. Using the author ordering, we can measure how applied (science) vs. theoretical (math) a conference is.

Reproducing the 1992 Results

Following Appel’s approach, I recreated the algorithm to compute the most likely proportion of mathematicians to scientists in each conference, with associated error bars. The code can be found at this Git repo. The data for these conferences was collected from DBLP (copy and pasted, then cleaned up using emacs macros).

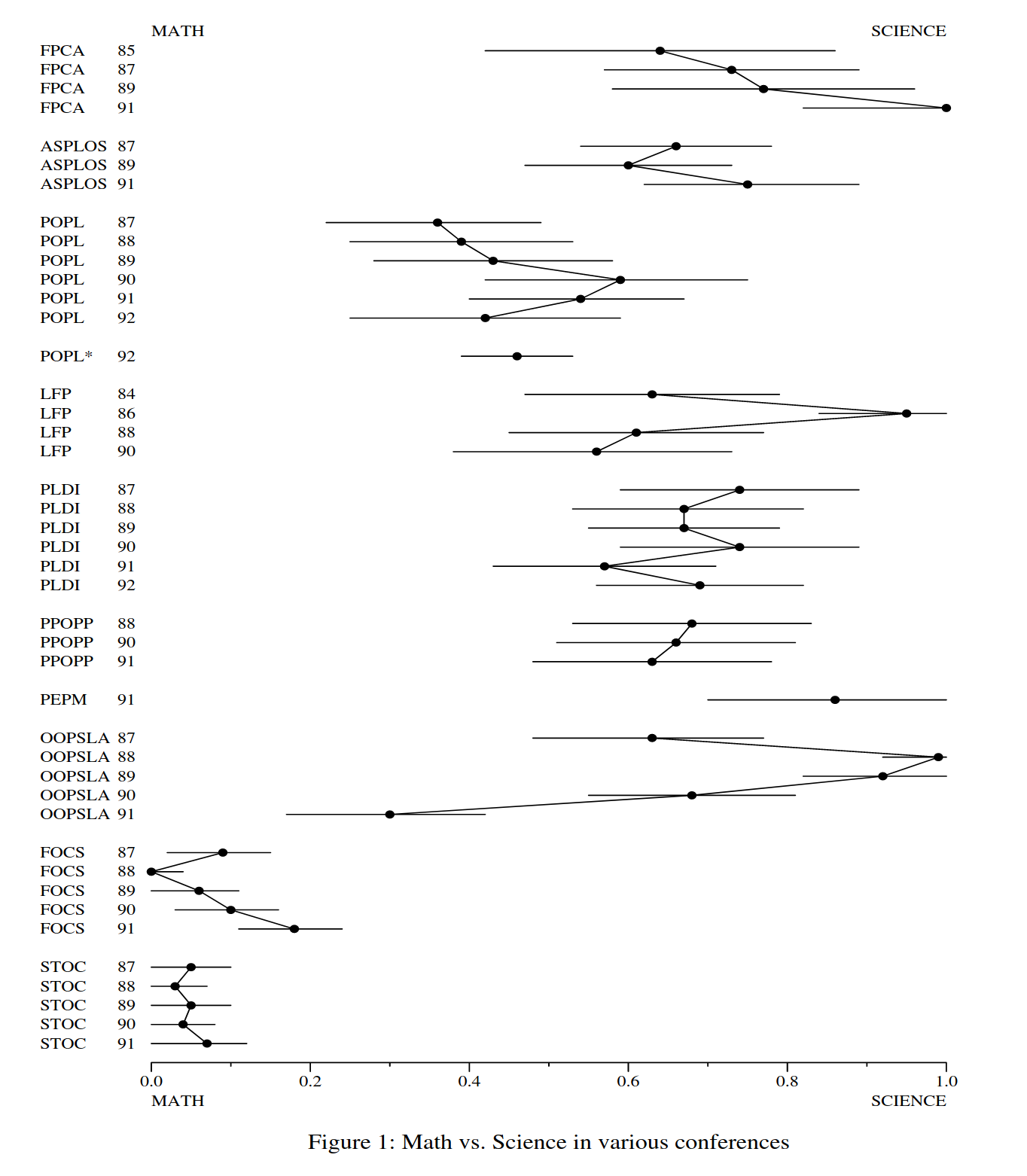

The original plot:

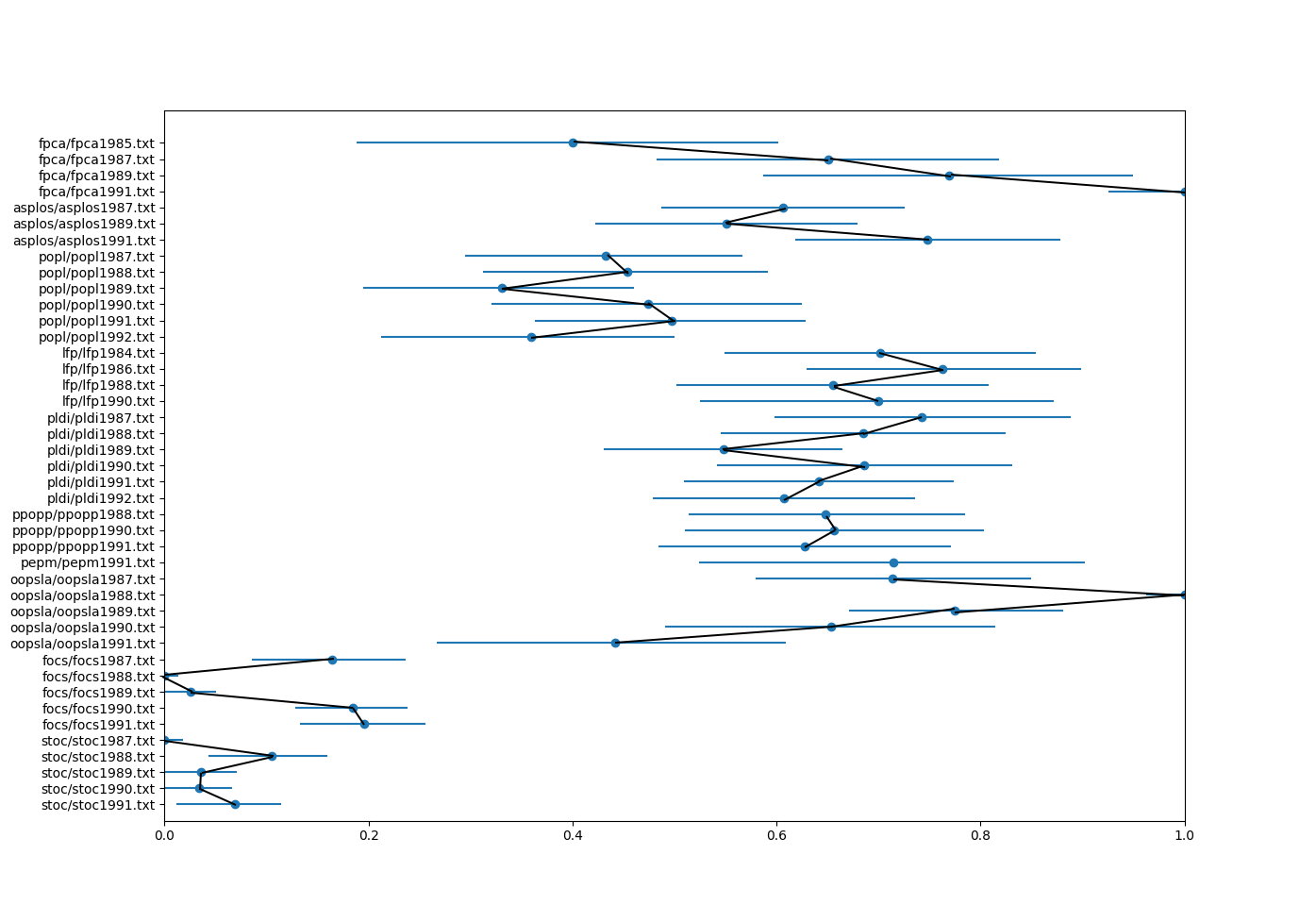

My plot, with sloppy manually-added lines:

If you look closely at the data, you may notice that many of my results differ from Appel’s original paper. I had a hard time figuring out the reasons for this. One possible reason is that sometimes surnames are difficult to discern. My code uses the probablepeople library to guess the surname portion of the name, and sometimes I have to decide when the library can’t figure it out, for example by manually removing whitespace or adding hyphenation in a name. However, I tried different hyphenation and whitespace combinations for the POPL authors, with no success in reproducing the original paper’s results. Note that this may still be a factor for other conferences, which I didn’t look at in detail.

My second hypothesis was that the DBLP data differed from the actual author lists that Appel used in 1992. To test this, I needed a paper copy of the proceedings, since the digital copies on the ACM digital library did not include front matter, and only the individual papers. I could have looked at each paper individually for the author lists, but I deemed that to be too much work. Instead, I found a copy of one of the POPL proceedings in the Penn library, and requested for the table of contents to be scanned and sent to me. A few days later I confirmed that this was the source of the discrepency, at least for that specific data point. Some of the authors switched to publishing under a different surname, and DBLP displayed their most current name, even for older papers.

To make my work easier, I didn’t do anything to solve these two issues, so my results will differ from Appel’s original results. For the first, I didn’t do any special handling of surnames, taking the name that probablepeople returned, and only intervening if it could not determine a unique surname. For the second, I just used the DBLP data as-is.

Newer Data

Next, I ran the algorithm on modern data. The most difficult part was resolving name issues, when probablepeople could not figure out an author’s surname. When this happened, I looked up the author and tried to figure out their surname from their personal webpages. If their surname didn’t really matter, for example when the author list is clearly not alphabetical, I was less careful. This means that even for the same person, I would edit names inconsistently when it didn’t matter for alphabetical ordering. Apologies if you’re one of these authors, or if I messed up your name!

One interesting thing I learned while collecting the data is that many of the ACM conferences were consistently held in the US early on. I was surprised since some of the major conferences currently alternate (well, usually) between North American and non-North-American locations. I thought this was a tradition since the start, but this has only been happening for about 20 years. For example, PLDI was in North America for its first 22 iterations. POPL was in the US until the 14th in Munich, and did not leave the US again until the 24th POPL.

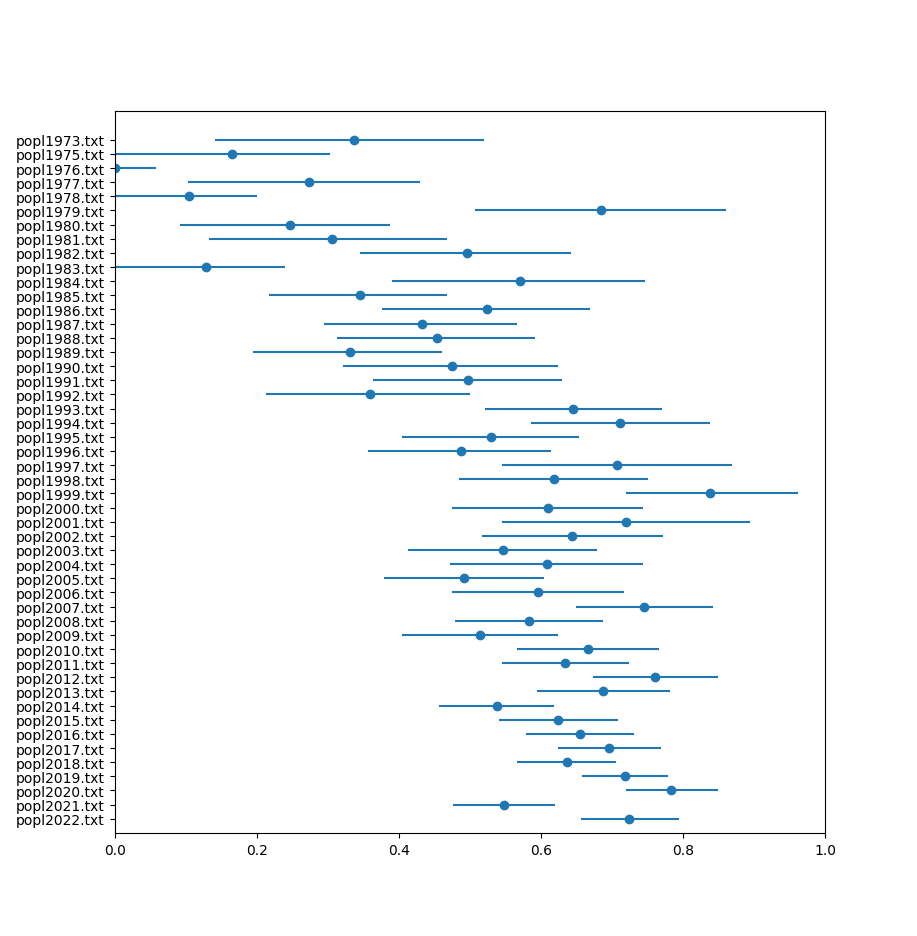

Finally, the results are plotted below. They suggest that POPL has been getting more practical over time, and that POPL is the most theoretical of the PL conferences, both of which I agree with.

POPL

The errors bars are far smaller nowadays, owing to the lower number of single-author papers and the higher overall number of papers presented each year.

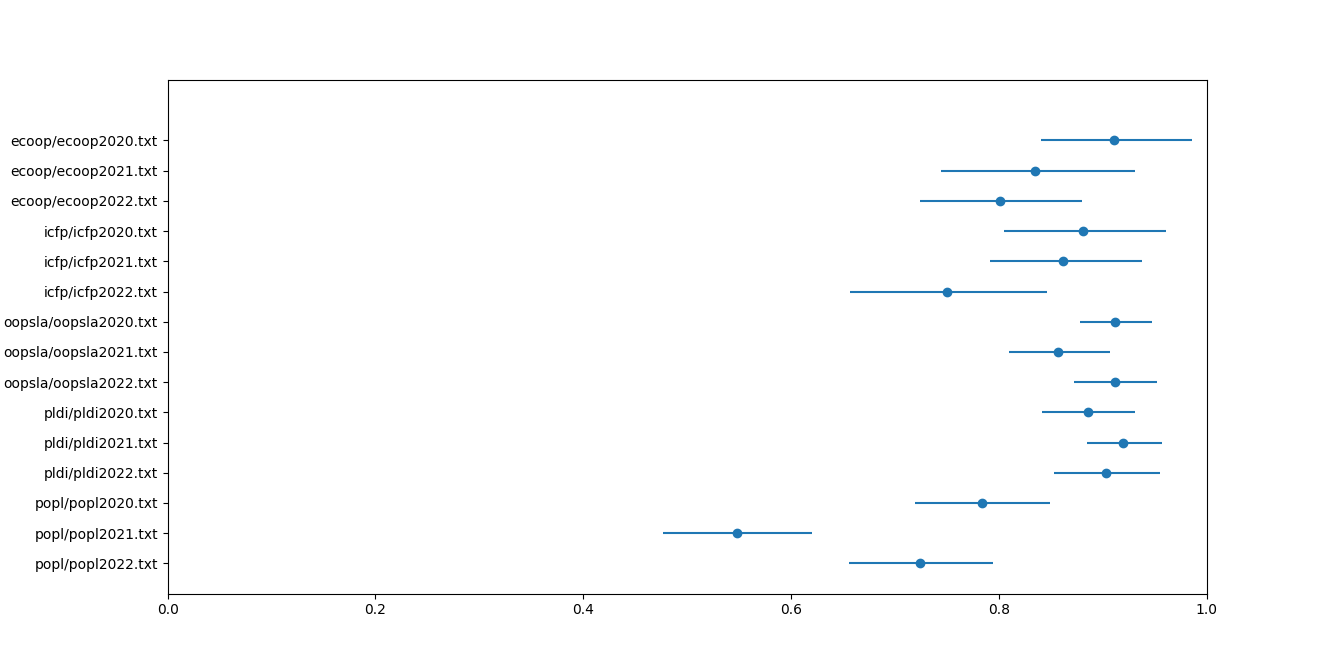

PL Conferences 2020–2022

Comments

person1: Great work!